Toxic Oysters, Exploited Children, and Dirty Water

High fever, severe stomach pains, diarrhea, and splotchy red rashes – the symptoms of typhoid fever are hard to miss. Spread through exposure to contaminated water, oysters became the unwitting cause of an epidemic of typhoid fever that ravaged the country in the late 1920s. In New York City alone, 150 people died in the winter of 1924-25. As news spread of sewage sludge sharing the same waterways from which oysters were harvested, what was once a food embraced by the masses were quickly and decisively regarded as public enemy number one.

Oysters, however, were not the only food under public health scrutiny. Unsanitary meat processing practices highlighted in the (fictional) book The Jungle (1905), spoiled milk, and botulism outbreaks had thrust food safety firmly into the public eye. With the rise of the home economics movement that blended “professional business” with “domestic affairs,” the concerns of the woman’s “home sphere” soon grew to encompass a wide range of social issues, like food safety, water quality, and child labor.

It just so happens that the oyster industry managed to encapsulate all three.

Food had been a central instigator for women’s movements dating back to at least the French Revolution (1789-99) when women marched to the Palace of Versailles in response to drastic food shortages. Before the passing of the 20th Amendment, suffragists used hunger strikes as a way of capturing both public attention and sympathy. (In 1914, journalist Djuna Barnes even staged a “forced feeding,” a common government response to hunger strikes, to elicit support from outraged readers.)

When it came to foodborne illness, women-founded organizations like the National Consumers League (NCL) and Federated Women’s Clubs mobilized women to influence politics, even without the right to vote. The NCL conducted grocery store inspections and compiled a codebook that demystified food labels and expiration dates (which at the time were only known by store owners), setting the stage for what would be the 1906 Food and Drugs Act that banned misbranded or adulterated food, beverages, and drugs. Even at local levels, women were shaping legislation: physician Esther Pohl Lovejoy in Portland, Oregon, was able to successfully change milk regulations after publishing her paper Impure Milk and Infant Mortality in 1910.

Part of women reformers’ cache in advancing their sociopolitical charges was using what is now called “maternalist politics.” That is, framing the specific societal ills as moral challenges necessary to be addressed by women – with special attention paid to the motherly bonds underpinning their demands. Child welfare not only nestled perfectly into this larger message, but commanded immediate, emotional reactions.

The Industrial Revolution of the 1870s had dramatically changed the landscape of cities across the U.S., and demand was surging for low-paid labor. In 1900, 18% of all American workers were under 16. Only 51% of white school-age children and 28% of their Black counterparts were enrolled in school, as more and more young children went to work in factories, processing plants, and coal mines instead. At oyster processing companies, children were paid as little as 60 cents a day (roughly $10 today), and women not much more.

And where were all these oysters headed, exactly? Whole, shucked (chilled and uncooked, marketed as “raw”), as well as steam-cooked (or “canned”) oysters, were loaded onto specially-designed “oyster cars” to be delivered, by rail, to faraway states of the U.S. west like Arizona and Wyoming also hit with the oyster craze. It was another mundane activity that hinted at major changes in store for the women’s movement: the growing economic and political power of the western states, and the Democratic Party’s appeals to draw in this new voting bloc.

Long before women formed the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) in 1904, state-level women’s groups like trade unions had been agitating for minimum age laws. Massachusetts was the first state in 1836 to pass legislation requiring workers to be at least 15 and attend school 3 months a year, later following up in 1842 with a limit of children’s work days to 10 hours. But these rules were rarely enforced in practice, pushing women to demand oversight at a federal level. Fortunately for them, the expansion of government power over social issues was a key theme in both Republican and Democratic politicking of the time.

Initially, Republican policies of the 1860s and 70s to enact federal aid for social services like the railroad, universities, and (primarily white) western settlers were met with resistance from the Democrats. But when the unintended impact of these policies largely benefitted larger companies – banks, rail conglomerates, manufacturing factories – instead of individuals and small businesses, the Democratic Party began to espouse more values of social justice in an attempt to win over those same western voters now frustrated by the lack of governmental support. A similar tension was unfolding in the post-Civil War south, where the same Republican Party that championed to end slavery was quietly condoning Jim Crow laws and the Black Codes. With both parties testing out the rhetoric of federal responsibility to attract western and African American voters – while attempting to avoid alienating existing white men voters – child labor was an issue that reached across the aisle.

In 1916, Democratic President Wilson signed into law the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act after much campaigning from the NCLC. This banned the sale of products that had been made with labor from children under 14 – notably making it illegal for interstate trade of these goods. It was quickly struck down by the Supreme Court – staunchly pro-business at the time – and replaced by the Child Labor Tax Law (1919), which taxed the net profits of employers using child labor. (This was again declared unconstitutional in 1922.) Under Republican President Coolidge, the Child Labor Amendment – a proposal for expanding Congressional power to “limit, regulate, and prohibit the labor of persons under eighteen years of age” at a federal level – was submitted to the states for ratification. (It was only ratified by 14 states.)

Despite these setbacks, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s term, social justice – and especially labor protections – had become a firm part of the Democratic platform. With his political reinforcement, significant changes like the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act – which prohibited “oppressive child labor” – and the landmark West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish decision – which granted backpay to a woman named Elsie Parrish on the grounds of a new minimum wage law being signed into Washington state law – were finally instituted.

Contrary to the standard narrative of suffrage dominating the early feminist movement, the triangulation of food, water, and child protection in women’s issues had taken root well before the second wave of feminism in the 1960s. Keeping with food safety and child protection, water quality concerns were encapsulated within calls for clean and sanitary kitchens and homes. This was in stark contrast to existing norms, where dumping human waste from buckets and bedpans onto city streets was routine, and waterborne diseases like cholera and yellow fever being transmitted from nearby waterways were also common.

One of the very founders of the home economics movement, chemist Ellen Swallow Richards, was also the first person to systematically test local waters for pollution, per request by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1887. Of the 20,000 plus samples of drinking water she generated in the two-year span, a shocking number was identified as being polluted by industrial waste and sewage. (In response, sewage treatment facilities began to open across the country, starting with Lowell, MA.) Richards’ use of the term “ecology,” and especially “home ecology” (which was later replaced by “home economics”), soon became a defining feature of her work and values; rather than referring to the passive study of relationships in nature, she advocated for analyzing how humans were changing (and often damaging) their environments –and inevitably affecting their quality of life.

The deteriorating image of the city due to outbreaks like oyster-induced typhoid in 1925, combined with growing concerns about rapid deforestation and depletion of environmental reserves due to large-scale industries like timber or natural gas, catapulted the conversation of conservation (intentional, respectful use) or preservation (protection from use) of natural resources onto political memos. Over a million women across the country joined women’s clubs, each with specific committees dedicated to preserving outdoor habitats and purifying urban environments. (These predated the Sierra Club, which was founded in 1892 and is now the nation’s largest environmental organization.)

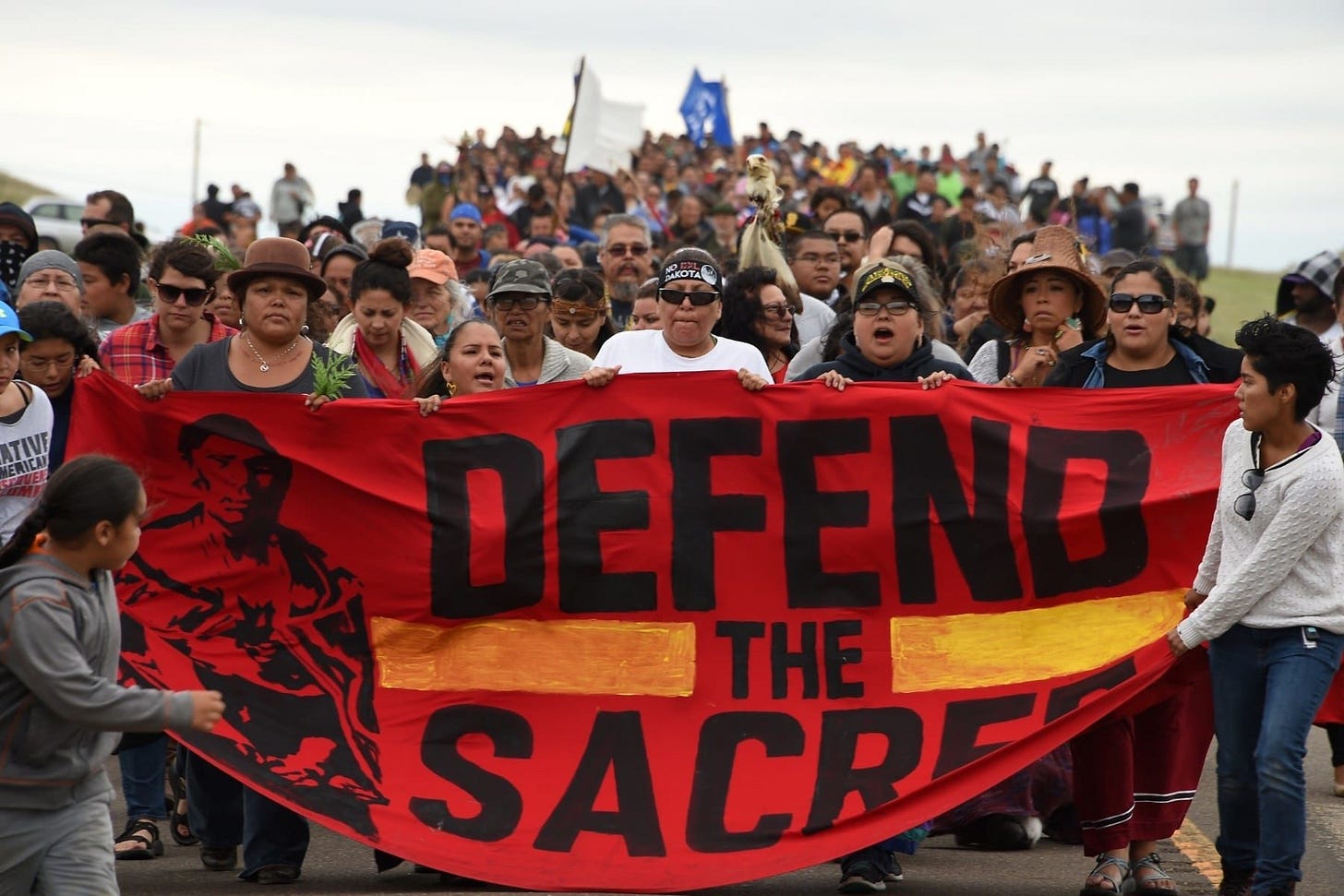

Yet these same activists – white, middle and upper-middle-class white women with the money and connections to access media and politics – actively excluded Black and Indigenous women from their efforts. In 1902, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs – which served as a network for various women’s clubs – refused to accept Black suffragist Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin on account of her representing an all-Black (versus an integrated) women’s club. The erasure of these perspectives has had lasting implications on the trajectory of environmentalism to this day: issues of contaminated water have been generally resolved in majority-white areas, but potable water remains an issue in places like Flint, Michigan, or along the (prone to leaking) Dakota Access Pipeline on Indigenous reservations in South Dakota.

The same romantic renderings of scenic “American wilderness” that drew public support for the creation of city-level, State, and National Parks also carried with them distinctly racist undertones. To establish National Parks like Olympic in Washington state, the Indigenous nations of the Hoh, Jamestown S’Klallam, Elwha Klallam, Makah, Port Gamble S’Klallam, Quileute, Quinault, and Skokomish were forcibly removed or denied entry to areas they once lived, hunted, or used for community and ceremonial purposes. There lies an inconvenient irony that much of the need for Olympic conservation came about due to settlers’ exploitation of the fruits of the land, including waterways once brimming with the native Olympia oyster; yet to achieve this goal, the original caretakers of the land “must” be pushed out.

In cities, large plots of land were carved off for new urban parks, built to channel the pastoral energy of the countryside, and situated at the edges of cities where working-class residents would have difficulty reaching them. For its newly-appointed protectors, the idyllic wilderness – natural or human-made – constituted a physical and metaphorical escape from crowded cities full of non-white, lower-class bodies. But that isn’t to say all the outdoors were white spaces: getaways like American Beach in Florida were havens for (more affluent) Black Americans during the Jim Crow era, and have since been assimilated into the National Park Service thanks to MaVynee Betsch (aka The Beach Lady)’s tireless environmental advocacy.

While perhaps not in the most flattering way, the humble oyster once again proved resourceful in highlighting the complexity and extensiveness of women’s activism in early feminism. Their work on these fronts continued well into the 1960s, when another electrifying debate sharpened the movement’s focus: reproductive rights.

Read Pt. 1: Recipes of A Certain Class

Read Pt. 2.1: Temperance, Morality, and the Red Balloon

No memes or status updates with this newsletter since I managed to publish two in a week! Stay tuned for more snippets of this book proposal.