Update: Recipe has now been evaluated against several bowls of luo si fen, and I am still feeling pretty good about it!

This recipe series is about cooking based on Wikipedia. Does that sound like a bad idea? I assure you it is! But how else am I supposed to sample something I can’t find a recipe for, and no restaurant near me serves? After all, I want to suffer on Lunar New Year! Enter: luó sī fěn, 螺螄粉, or snail noodle soup, except an imagined version from my brain as I have no idea what it actually tastes like.

Also, I know I’m very late on this recipe, and I’m sorry. To be honest, I almost pressed publish on this last week to meet my own arbitrary deadlines. But it felt wrong to give you all a recipe that wasn’t totally vetted, so I listened to my gut, waited, and cooked a few more iterations.

So with that…happy Year of the Tiger! I hope this recipe gives you some adequate happy-suffering to start the year. And if you want to read an essay I wrote last year about LNY for TODAY, you can find it here: Celebrating Lunar New Year As An Act of Resistance.

First, some context:

For the last few months, I’ve been down a rabbit hole trying to make luó sī fěn, 螺螄粉, literally translated as “snail rice noodle.” It’s a specialty dish hailing from Liuzhou, a city in Guangxi, a southern region of China bordering Vietnam that boasts steep mountains and intersecting rivers. The dish captures the geography of the area well: river snails perfume the broth; the noodles are made from rice given the prevalence of rice paddies (you may recognize the picturesque Longsheng rice terraces located in nearby Guilin); and of course, the pickled bamboo shoots, which grow well in the climate, that give the dish its signature stink—earning its name as the “durian of soup.”

There are multiple stories about how luo si fen came to be, generally accepted that it was conceived sometime in the 70s or 80s. According to the government, the dish combines “traditional food materials of the Han people with the Miao and the Dong ethnic groups.” Despite having been around for decades, luo si fen only saw a meteoric rise in the past few years due to high-end packaging technology. Instant luo si fen—as in prepackaged—has become a quarantine luxury, each parcel comprised of an entire orchestra of smaller plastic packages. Dried noodles, soup base, bamboo shoot, fried tofu skin, peanuts, pickled cow bean, and the toppings go on. In 2020, instant luo si fen captured $1.5 billion in Chinese sales alone. (For comparison, Nongshim, the world’s 5th largest ramen company and the makers of Shin ramyun and Parasite-famous Chapaguri, sold $1.85 billion instant noodles worldwide in 2020.)

Naturally, when I came across luo si fen online, I knew I needed to try it. The small problem is…almost no restaurants in the U.S. serve it, and none near me. The few instances of stateside coverage have been of now-closed spots; the only one that seems still open is in Virginia. So…the only option was to make the dish myself if I wanted to eat it. [Update: Instagram fam always coming through with hot tips! Qin West Noodle in LA serves luo si fen, as does Chili Square in Boston. I have now had both, and still feel good about this recipe.]

As you probably gleaned from my long treatise on shrimp chips, I like to have multiple data points before I cook something. (The same is true when I go out to eat—I call my process the “Yelp-critic-Instagram triangulation.”) So the first thing I did was to get my hands on as many instant luo si fen packets as possible. While doing so, I also managed to convince my Serious Eats editor, Daniel, to spend over $50 in snail noodle products. Here’s photo proof of his excursion, attached to an email with the subject line “This is your fault.”

I regret to report these packets tasted overwhelmingly like bamboo shoot, and not of much else. (I guess that makes me an instant luo si fen hater. Sorry!) But all the luo si fen coverage waxed on about the lush broth made of “pork bones, chicken bones, and river snails.” So I turned to my mother, asking her to search Baidu (Chinese Google) for a luo si fen recipe—to little success. Even endless YouTube scrolling turned up only recipes and reviews of instant luo si fen brands; the only video “recipe” I found was a dreamy sequence from Li Ziqi, a Chinese vlogging megastar that lives in an idyllic cottage surrounded by actual bamboo (which she then harvests and ferments):

Note: This video has a casual 69 million views.

So basically, all I had to start my luo si fen journey was an active imagination, a few bellies’ worths of subpar instant luo si fen, and Wikipedia. Here’s what it says about the soup:

“The stock that forms the soup is made by stewing river snails and pork bones for several hours with black cardamom, fennel seed, dried tangerine peel, cassia bark, cloves, white pepper, bay leaf, licorice root, sand ginger, and star anise. It usually does not contain snail meat, but it is instead served with pickled bamboo shoot, pickled green beans, shredded wood ear, fu zhu, fresh green vegetables, peanuts, and chili oil added to the soup.”

Okay, that’s fairly detailed for Wikipedia. But the question remains, if I’m trying to make a recipe for something I’ve never tasted, and probably will not taste for quite some time, how will I know if I get it “right?”

This conundrum has pressed me to think a little more critically about what it means to develop a recipe, and what the heck recipes are (beyond literal instructions to make something, of course). As I stirred my many pots of snails and pondered the question, “What should this taste like?” it occurred to me that I was actually trying to ask, “How do I think this is supposed to feel like?”

I mean this in a sensory way, not a romantic one. When I eat, say, cheung fun at my favorite dim sum place, I feel the supple rice noodles slip and slide between my teeth, perhaps accentuated by the bracing saltiness of some soy sauce squirted on top. This likely spurs me to suck on my cheeks just a little as I chew, with a little inhale to help dissipate that salinity. Or maybe I’m feeling the caramelized, sweetened note of a soy sauce that’s been stir-fried with the noodles, the soft crust formed through this interplay of ingredients nestling into little crevasses of my teeth. This all builds into a complete sensory package that I tuck away, to be retrieved as reference data if I ever were to make cheung fun.

A recipe, then, could be understood as an individual’s best approximation to replicate a certain sensory experience. And a good recipe is one that consistently captures that experience. This is a straightforward (though not necessarily easy) process for dishes I’ve eaten before, and know what to build towards. But for dishes like this mythical luo si fen, how do I determine what sensory experience I should model the recipe after? This prompted me to reflect on how I began concocting my own sensory interpretation of luo si fen, independent of tasting it. That would’ve been the first time I read Goldthread’s media coverage of the soup, when I began to attach physical reactions to the passages on my screen:

For those who love it, the smell of luosifen is heaven, enough to make the mouth water. For others, its acerbic stench has been compared to a “chemical bomb.”

When I loll around words like “pungent,” or in this case, “acerbic” in my mind, it gives me a specific feeling in my spine. It makes me want to lean back and breathe a sharp exhale like a soothing cleanse. Mentally, I know this is in sharp contrast to a description like “moldy and soft,” to which I would flair my nostrils and push air around in a circle to get a deeper whiff as I eat.

And here’s another clue, from the same piece:

Growing up in Liuzhou, many of my hometown memories are tied to luosifen. It was the go-to comfort food after a long day, best enjoyed with cold soy milk.

What a wrinkle thrown into the mix! My initial mental queries of luo si fen most certainly would not taste good with soy milk—I had a visceral, disgusted reaction reading this the first time, although I had never sampled the pairing before.

In a bizarre way, for a soup I know very little about, I quite easily plucked little ‘clues’ on how I thought it would feel. All my imagined sensory details of what this soup “should” illicit became the goalposts my recipe approximated towards. Whether or not these goalposts are correct, I have no idea, but this little thought exercise made me revel in the fact that all art forms—from composed dishes to musical scores and architectural blueprints—are sensory recipes. How extremely awesome is it that we humans have the ability not only to dream up abstract sensory ideas, but to translate them into recipes that invite others to participate and enjoy the experience we created?

Okay so #blessed vibes aside, where did that lead me when it comes to luo si fen. All these feelings made it feel far too daunting to carry out all the pieces of this noodle soup simultaneously, so I decided to start with the broth. Some of the sensory clues I anchored on were:

Creaminess. The visual of Li Ziqi’s soup made it clear that this was a broth made from a hard boil, which would emulsify the fat into the broth and leave nice smoothness on the tongue. Looking at the color, it seems the bones may not have been roasted—so I opted to create a base from un-roasted pork neck bone (a very classic broth base for Chinese soups) and chicken feet (for silky collagen).

Snail flavor. I imagined a certain gnashing of the teeth here: there’s a certain acrid sensation I get when eating snails, which I wanted to capture—but mediate. The first time I dumped 2 pounds of snails into the pot, I felt a slight sinking feeling it was too much. And indeed, it was.

Pairs with soy milk? This clue made me feel there must be a note in the luo si fen that harmonizes with the sweet, floral nuttiness of good soymilk. The first few times, I went in hard with sand ginger. This created a powerful perfume in the broth that prompted the same sort of drooling sensation as tonic water (not in a good way). When I tried to do this with more licorice and less sand ginger, the broth became far too woodsy, feeling like spikes along the back of the throat. Ultimately, I ended up wrapping both herbs in a sachet, so I had more control over the infusion, and that worked much better.

Fragrant. This term is fairly generic, and produces little sensory feelings for me. (Perhaps this is what we mean when we say we are desensitized to something?) But it did make me think 1) there should be some easy-to-place top notes in the broth, so I upped the ratio for tangerine peel and star anise compared to the other spices, and 2) the spices should probably be bloomed in oil to extract maximum aromas. After a first few overly eager tries, I also lowered the total amount of spices a bit (because drinking a small bowl of the final broth felt like licking potpourri) and managed to get a broth that, for some reason, emitted a nicely roasted peanut smell.

After all that imagining and replicating, this recipe is what I’ve got. I’m not going to call it luo si fen because I don’t think that’s responsible. It’s an approximation of the feelings I’ve had reading about, and looking at, luo si fen from afar. I have no idea if this is “accurate.” But for now, I think it tastes pretty damn good when compiled with store-bought toppings. (We’ll see if I still feel so confident once the from-scratch toppings are incorporated.) Stay tuned as I tackle the bamboo shoots next!

Pork, Snail, Chicken Broth for an imagined luo si fen

Yield: 2.5Q

This recipe gets a 3/10 because it’s not hard to make, but the ingredients are quite specific to procure. You’ll have to go to a Chinese grocery store like 99 Ranch that has a dried herbs and spices section.

Ingredients

2 lbs pork neck bone

1.5 lb chicken feet

1 lb periwinkle snails

2 Tbsp neutral oil | Note: I use vegetable oil

5 cloves garlic, peeled, sliced (15g)

8 scallions, stemmed, chopped (70g)

2” knub ginger, peeled, sliced (10g)

2 pieces dried tangerine peel (6g)

4g cassia bark (aka Chinese cinnamon)

2g whole dried sand ginger

1g dried, sliced licorice root

2 dried bay leaves

2 whole black cardamom (1g)

8 whole cloves | Note: I use Diaspora Co.

7 whole star anise (4g) | Note: I use Burlap & Barrel

1/2 tsp whole fennel seeds | Note: I use Burlap & Barrel

1/4 tsp whole fermented white pepper | Note: white peppercorn sold in Asian grocery stores are usually fermented a few weeks longer than those in western grocery stores. I use Burlap & Barrel.

1 Tbsp shaoxing wine

3 tsp kosher salt | Note: I use Morton’s Coarse

5Q water

Instructions

Combine pork neck bone and chicken feet in a pot with enough cold water to cover. Bring to a boil over high heat, and let boil 10 minutes. Strain from water, rinse, and reserve. Note: This is to remove some of that initial scum from the bones.

Place periwinkle snails in a pot with enough cold water to cover. Bring to a boil over high heat, and let boil 10 minutes. Strain from water, rinse, and reserve. Note: This is to remove some of the initial muddiness from the snails.

Combine tangerine peel, cassia bark, sand ginger, and licorice in a small bowl. Pour hot water to cover, and let steep 3 minutes. Strain, rinse, and wrap up in a small sachet. Note: This is to remove any dirt or debris. | Note 2: The sachet allows for easier removal later on, as these herbs grow more bitter and perfumed over the cooking process.

Heat oil in an 8Q (or larger) stock pot over medium heat until slick and shiny. Add garlic, scallions, ginger and sauté 2-3 minutes until fragrant.

Add bay leaves, black cardamom, cloves, star anise, fennel seed, white pepper and sauté 30 seconds.

Add pork bones, chicken feet, and periwinkle. Stir.

Deglaze with shaoxing wine, and let reduce 30 seconds.

Add salt, water, and the sachet.

Slowly bring mixture to a boil on medium heat, skimming all the scum that forms on top. Let boil 45 minutes.

Remove sachet, and reserve.

Cover pot, and lower heat to a stage where the broth is at a soft boil while covered. Let cook 2 hours, intermittently checking the broth and sampling it. Note: You can remove some of the meat off the pork neck bone after ~2 hours to eat. I have nice memories of chowing down on this with a splash of soy when my mother made soup for our family growing up, so even at times I’ve totally overcooked the meat I still fish it out and eat it.

Let broth cook another 6-10 hours, or until it has roughly reduced by half. (My final yield was ~2.5Q.) Note: You can add the sachet back at any point for a more pronounced herbal flavor, but please be mindful as it can get super perfumed, fast—I recommend only doing so in doses of 15 minutes at a time.

Uncover pot, and sample broth again. If you would like it creamier, bring it to a rolling boil and let reduce until you are satisfied. If it feels good as-is, strain and season to taste.

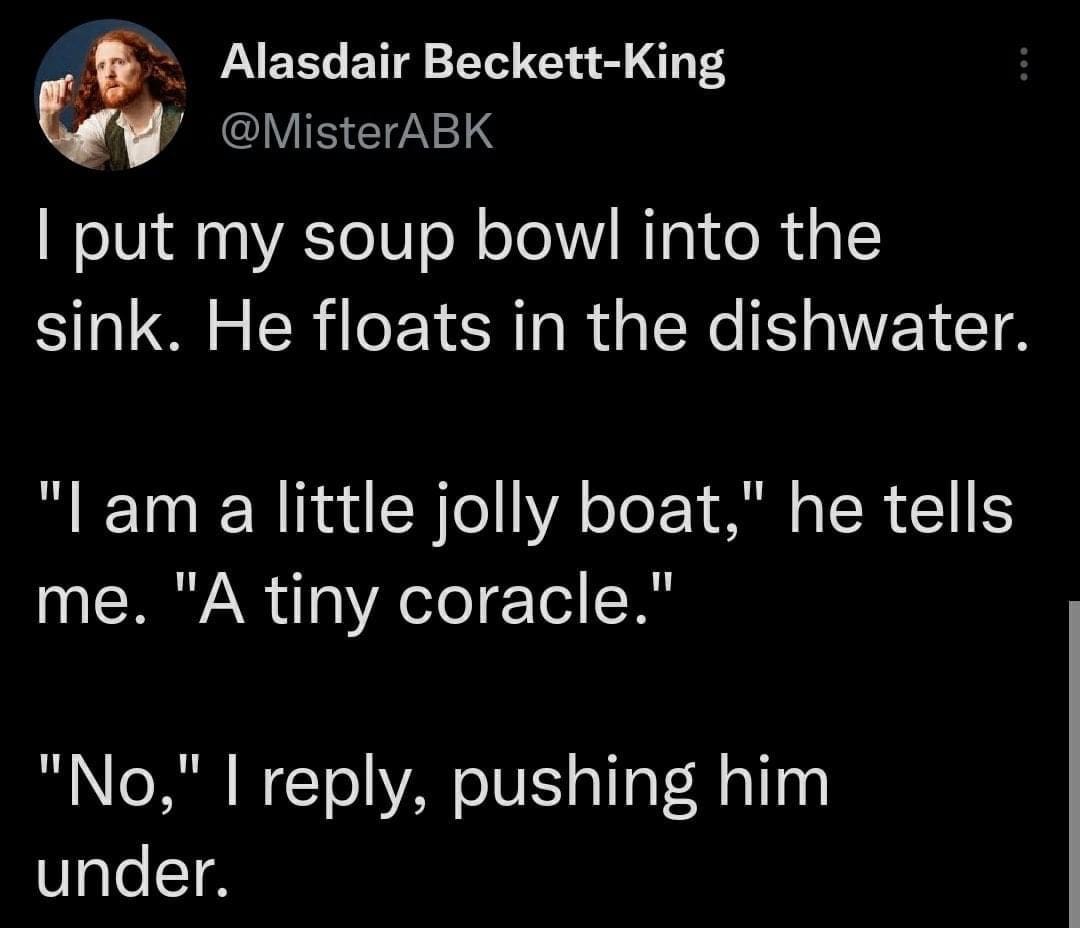

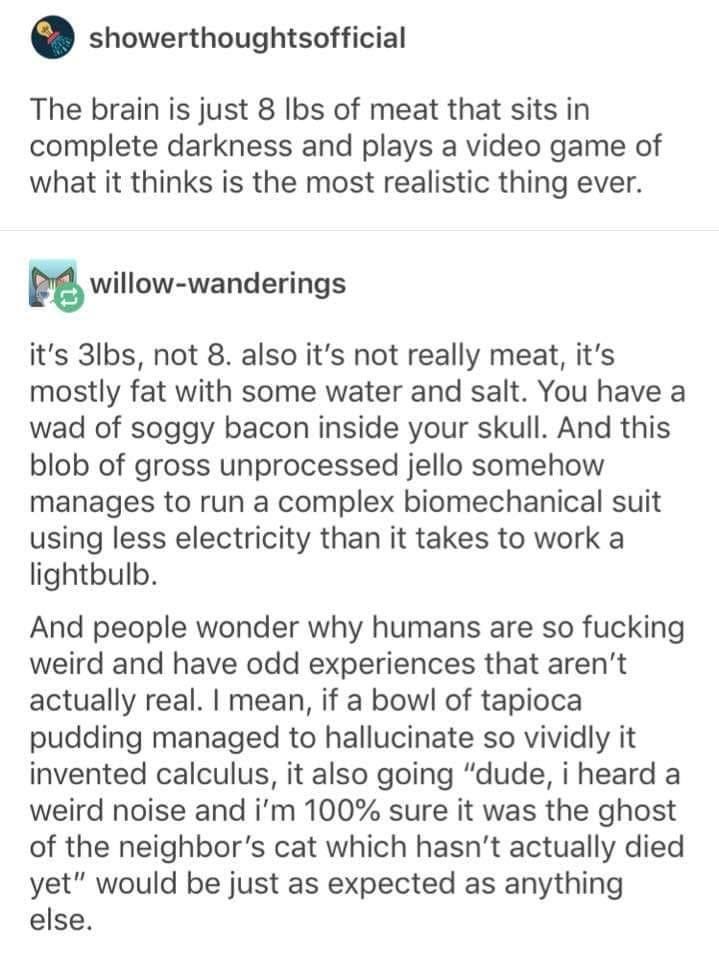

Weekly Meme Roundup

Personal Things From This Week

Listening to: Pop Punk of the 2000’s on Spotify after seeing news of the When We Were Young festival. (Unclear if it’s real or not, but if real the lineup is basically my middle school fever dream.)

Watching: Sword Snow Stride, upon my team member Edric’s suggestion; finally finished Wind from Luoyang.

Reading: Children of Blood and Bone by Tomi Adeyemi; just finished Legend by Marie Lu.

Eating: Exponentially increasing mounds of dumplings!!!

Drinking: MUD/WTR, the coffee replacement I keep trying to persuade my team to drink. (I worry my enthusiasm for the product has made them suspicious it’s a Ponzi scheme.)

Nice thing I did for myself this last week: Took a night off, when I was supposed to be writing this newsletter (heh…)