The realities of writing a cookbook for hire

Plus, the most complicated recipes from my grilling cookbook

Update: You can also watch this newsletter via my IG Reels or TikTok

To date, I have written 7 cookbooks. All of them have been commissioned, meaning the publishers sought me out as the author (and usually, the recipe developer and photographer) versus me finding an agent, submitting a proposal, and having a publisher bid on the book idea. This “for hire” situation might sound ideal, but let me assure you it is not. After stewing on this idea for years (and stepping away from this work completely), I’ve decided to break down the process for others who may be considering doing this sort of work, so they can at least enter in an informed way.

Falling into the indie publisher world

I started writing cookbooks back in 2015, as a young and eager recipe developer who wanted to gain credibility in the world of writing. I had signed on to recipe test for Storebound, a kitchen gadgets company, and this turned into an assignment to write a good chunk of recipes for their limited-release, self-published cookbook. I was paid $300-$600 per recipe and photo, credited on the cover, and given no royalties. All things considered, this was a pretty decent gig at the time — and they had a team to handle tasks like editing (for words and photography). I’m not going to dwell on this beyond the fact this sort of arrangement exists.

After that, I hopped onto a few projects at indie publishers like Skyhorse Publishing and Ulysses Press. These places generally commission book topics based on what is trending online. If you search terms like “keto cookbook” and look at top sellers, there are plenty of these publishers up there — proving that even the cheesiest-looking titles can make a sizable return if the conditions are right. Achieving this, however, requires high volume and low costs. These places tend to have a lot of book topics in their lineup, held in anticipation of enough public interest to greenlight. The physical books themselves are fairly mediocre; the image quality is low, and the overall materials used are akin to the drywall you see in those fast-built new condos.

But more (most?) importantly, these publishers have a robust list of freelance authors they can call upon to do all sorts of topics. While some writers may have specialties they declare, it seemed for the most part that folks were treated as generalists. I know I was — I signed on to do my first book (on pressure cookers) after seeing a public request for applications, and during that time was also considered for a book on ice cubes (?), one on baking in muffin tins (?) and some other titles. There was no real vetting as part of this process, and I’m not sure what credentials or “proof” of skill is actually needed to be an author, recipe developer, or photographer — hence the dramatic variability in the quality of books in even a single publisher’s portfolio.

Calculating how much it actually costs to write one of these cookbooks

Once you are selected as the official author for a cookbook, you do receive a proper advance, or the lump sum you’ve given in advance of the book being published, to cover the time and costs (e.g., ingredients, equipment) incurred for creating the content in the first place. My first advance was $2.5K, others were $3K, $5K, $7K, $10K, and $20K. (I cannot specify which was which due to NDAs I’ve signed.) You also receive royalties, which are a percentage of the book’s sales (either gross or net — before or after costs), paid to you into perpetuity (forever), usually in biannual or annual increments. My royalties have ranged from 2% to 25% net.

PSA: Always, always, always demand royalties! There are publishers that will try to lure emerging writers without agents with book contracts that don’t include royalties. This offers you no upside if your book does happen to do well! (And yes, I absolutely did have a publisher try to pull this on me.)

These dollar amounts seem decent until you really think about the task at hand. As the author, you need to:

Create (ideate, test, and document) 50-60 recipes

Write 100-400 words about each recipe for the headnote

Photograph each recipe (so cook, food/prop style, and shoot)

That’s four different jobs being done by one person — and that doesn’t even include the costs of groceries. Depending on what you consider billable time, you may find that these books literally net out at zero.

Additionally, you can pretty much bank on the fact that there will be no royalties coming — ever. Royalties are first deducted against your advance, so the dollar amount of royalties you are owed must be more than the advance you were paid for you to receive any additional money. The first of the books I ever wrote has sold only a few over 300 copies; another out for about 2 years just under 1,000.

(One exception to this has been my Avatar the Last Airbender cookbook, given the show’s fanbase. I just received my royalties statement for sales since it was published November 2021, and it’s sold 50K+ copies.)

These figures are not unusual: the average amount of sales per book in the U.S. is just around 500. Even celebrities can’t seem to sell books these days. (Did you know that in order to get on the New York Times bestseller list, you only need to sell 5-10K copies?) There’s also a steep dropoff after the first few months and definitely the first year, so at this point, I feel fairly certain I won’t be receiving a royalty on many of these books, as they will likely be discontinued before the math works out in my favor.

Trying to “do it right” with major time constraints

In order to meet the volume demands to keep these small publishing houses running, the turnaround time on commissioned books is incredibly short. I’m talking 3 months, up to maybe 6, between the signing of your contract and the deliverable of the entire manuscript and photos. That includes the time you need to pitch your ideas for review by your editor. While these indie places tend to be fairly lenient, they ultimately hold the power to say “no” to recipes and request drastic changes to your direction. So at the low end, you have 90 days to create, write, and shoot 50 recipes — under 2 days per recipe.

I think it’s fairly obvious this is not enough time. So you’re faced with the choice of what you’ll prioritize. Sometimes, it meant I tested the recipe a few extra times, allocating the money to groceries instead of that extra-special prop or more photography takes. Sometimes I spent extra time researching the origins of an ingredient or technique to write a respectful headnote, at the expense of a more ‘innovative’ recipe idea.

There is a certain amount of sloppiness that this model is predicated on, because there are just so many concessions that must be made. The one that eats at me the most is definitely recipe accuracy and consistency; in such a rushed state, I need to immediately move on from a recipe after the first successful version, instead of being able to test it a few times for confirmation. I simply know there are issues with the recipes in the books I’ve written, but I didn’t have the time, money, or resources to find and correct them. Another is the photos — there are some I really invested energy into styling, and I still enjoy seeing the blown-up, physical versions of those; but many others were hastily done, a quick swap of the backdrop and surface without even changing the lighting or camera angle.

Rifling through other books, I’ve also been dismayed at the language used in certain headnotes because there is simply no good system of controls and standards. Just like the creation process, the editing timeline is extremely short. The editors are doing the best they can to ensure the book has no glaring errors, no mismatched ingredients/steps, no missing times, that sort of thing. It’s unlikely they have the headspace to be thinking about the repercussions of the white gaze or if something might be appropriative. And I think it goes without saying there’s no cross-testing, where someone else actually tests your recipes by following your directions as written and giving you feedback. (Cross-testing is the norm at places like Serious Eats, which is one of the reasons I enjoy working with them.)

The repercussions of having my name on a title published alongside some potentially extremely problematic stuff was something I started weighing really seriously a few years in, as social justice became a much bigger part of what I do within the food and beverage industry. Although I was getting bigger paychecks and still needed to pay rent, it started feeling less and less worthwhile. That being said, that decision looks different to everyone.

What happens once the book is actually published?

Unlike cookbooks from the bigger publishers like Phaidon or Penguin Randomhouse, most of these launches don’t see much of a marketing or PR campaign — if any at all. They may be released at certain times to capture favorable consumer activity — for example, my grilling book was released right before Memorial Day, the low-ABV cocktail book during Dry January — and there may be a press release that goes out, but there is definitely no budget for things like influencer gifting, book tours, or a launch party that’s standard practice for other places.

To be fair, you can see how the publisher is also carrying a large amount of risk, too, since they fronted the dollars for a book that may or may not sell well. But the lack of investment in a marketing rollout also creates a vicious cycle where the book likely won’t sell that well, save for the few unicorns that every publisher is chasing.

Now, what can you do knowing this information?

If you’re considering working on a commissioned cookbook, I hope you’ll consider some of the below:

Acquire an agent. This is hard because most authors with agents aren’t on the market for commissioned cookbooks, but see if you can at least have one review your contracts and help you negotiate them. (Remember that you should always be receiving an advance and royalties, and props/groceries expenses if possible.)

Share your rates publicly. Don’t sign NDAs that force you into silence. Get on #PublishingPaidMe and assess what others are being paid, and tell others what you were paid. Transparency helps everyone acquire better deals and expose unscrupulous publishers.

Establish the limitations of your deliverables. For example, explicitly stating you will only provide 1 photo per recipe, not 4 versions, and in what format. That your manuscript will come in a certain layout, and any reformatting is the responsibility of the editors. That your headnotes will be a maximum of x characters, and no more. That any requests for revisions will add x days to your final deadline. That sort of stuff.

If you’re a consumer of cookbooks, after reading this I hope you’ll think about:

Being a lot kinder to cookbook authors! Not only are a lot of the final factors that drive your experience with a book outside our control (e.g., issues with the paper, dents in shipping), but many of the other variables for making the book are also never in our favor. I recognize how frustrating it is to find mistakes or have recipes not quite work out for a cookbook you paid for, and you should absolutely still deliver this feedback via a public review, but consider how you go about delivering that message. (And maybe reconcile that with how much you paid for the book.)

Pay full price for books and buy them at smaller shops if you are able. So probably not Amazon (but I understand if that’s your default).

Ask for transparency from publishers. Just as food and beverage media has begun normalizing publishing the different editors and fact-checkers for a piece, we can and should demand publishers to reveal those involved in the production process so everything does not fall solely on the writer.

Demand more QTBIPOC authors at big publishing houses! I suffered through some pretty inequitable cookbooks for my resume, so I could show cookbook experience in future conversations with bigger publishing houses. That has paid off, but it doesn’t make this system okay. The sad reality is that QTBIPOC authors are asked to have a lot more of everything — credentials, followers, etc. — in order to land their first major contract. Publishers are risk-averse and will default to crowd-pleasing titles and safe authors, and I think we’re all aware of what that is “code” for.

Despite all the frustrations along the way, writing these cookbooks has been an important part of my personal learning and growth as a chef, recipe developer, and food photographer. (Not to mention cultivating extremely tight project and time management skills.) I had a really good time collaborating with my partner to write a cocktail book that’s fairly personal to us, which also stretched me to understand light in a new way so I could photograph beverages. I’ve felt very fortunate to hear people’s stories about their love for Avatar the Last Airbender Cookbook, and received some truly nice messages about the thought they noticed behind my recipes. Now that I have the privilege to step away from this kind of commissioned work, I’m appreciative they’ve gotten me to a place where I can discuss deals with bigger publishers. But gosh, do I wish I had asked for more.

P.S. Recipes below: Fennel & Coriander Rubbed Baby Back Ribs; Dairy-Free Sesame Scones with Smoky Blackberry Jam.

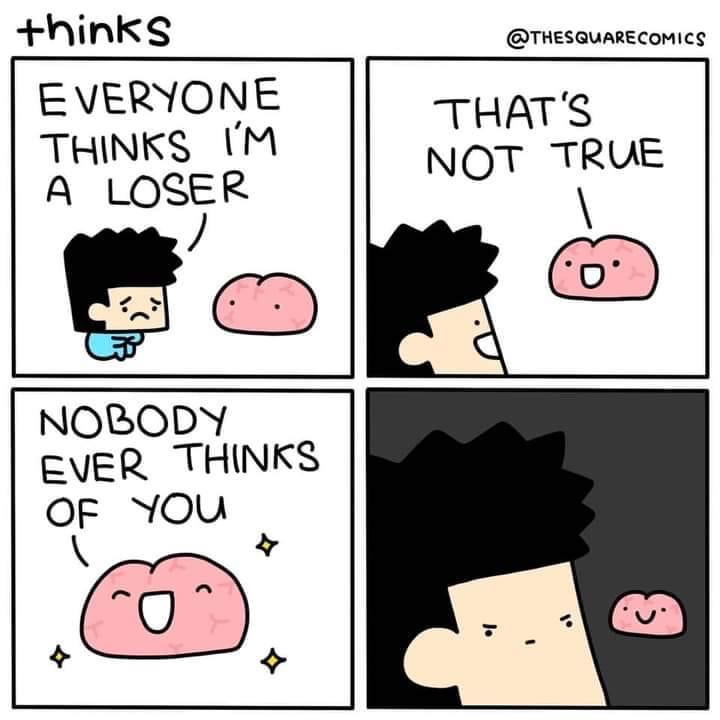

Meme Roundup

Personal Things from the Last Few Weeks

Listening to: 8D instrumental music! Wow this new sound technology is incredible!!!

Watching: TikTok, and not much else these days

Reading: A very long backlog of course texts. Here is a recent favorite.

Eating: Stir fry with Maui Nui venison

Drinking: Matcha lattes (here’s a simple recipe I wrote for EatingWell)

Nice thing I did for myself this week: Scheduled a day to go apple picking!

Fennel & Coriander Rubbed Baby Back Ribs

from The Infrared Grill Master

These are my crowd-pleasing ribs that I whip up anytime there’s a BBQ party among my circle of friends. They carry all the smoky meatiness guests are looking for in a riblet, but also an unexpected floral note and subtle sweetness that make them extremely craveable. One of my favorite experiments is to vary the type of wood chips I’m using while grilling this low-and-slow to the finish line, as it adds a different complexity to the ribs every time. If it’s your first time making ribs, make sure to keep an eye on these as they near the 1 hour line so you don’t overcook them – the meat should fork-tender, pull away easily from the bone but not fall off (that’s a misnomer!).

Yield: 1 rack baby back ribs

Ingredients

1 rack (roughly 2 lbs) baby back ribs

Brine

2 quarts water

1/3 cup kosher salt

¼ cup light brown sugar

4 cloves garlic, sliced

1 shallot, sliced

Dry Rub

1 tsp whole fennel seed

2 tsp whole juniper berry

1 tsp whole black pepper

½ tsp whole cumin seed

½ tsp whole nigella seed

1 tsp whole coriander seed

¼ tsp ground ancho chile

Grilling

1 Tbsp neutral oil

Basting

1 Tbsp maple syrup

½ cup apple cider vinegar

1 Tbsp soy sauce

Instructions

Whisk together ingredients for brine until salt and sugar fully dissolve. Place ribs and brine in suitably sized containers or sealable bags. Let brine 8 hours or overnight.

Remove ribs from brine and dry thoroughly with paper towels.

Preheat grill to 450F. Place wood chips of choice on the grill.

Combine all ingredients for the dry rub and grind in a spice grinder until coarsely ground. Rub over ribs, concave side first. This ensures spices will not stick to the board after the ribs are flipped.

Drizzle oil on the convex side of the ribs, until evenly distributed.

Place ribs on grill and cook, uncovered, 15 minutes or until the surface is lightly charred and spices have browned but not burnt.

Place ribs on the upper grill rack, away from the direct heat of the grill.

Turn grill temperature down to 350F, cover, and let cook 1 hour, or until meat is fork-tender and meat comes off easily from the bone.

Mix together maple syrup, apple cider vinegar, and soy sauce. Pour mixture over ribs 2-3x during the hour-long cook.

Remove ribs from grill and let rest 5 minutes before slicing into individual riblets.

Sesame Seed Scones with Smoky Berry Jam

from The Infrared Grill Master

If you aren’t already using a weight scale for baking, I encourage you to start now. Yes, you have to buy a small scale that calculates in grams (usually under $20 on Amazon), but just think: you’ll never need to level a cup of flour again, or dig out chunks of butter from a measuring cup. Your recipes will turn out accurately every time. To be honest with you, I don’t even bother following pastry recipes that aren’t measured in grams because they are fundamentally inaccurate, and baking is not like cooking where things can be adjusted as you go – so why bother? This scone recipe is one I’ve adapted from King Arthur Flour’s excellent (and well-measured) website. It’s a fantastic basic scone formulation that you can change up to your heart’s desire with nuts, seeds, fruits, extracts, and more. I’ve also made this dairy free so any lactose-intolerant guests don’t have to miss out!

Ingredients

Sesame Seed Scones

160g all purpose flour

50g white sugar

¼ tsp kosher salt

1 ½ tsp baking powder

60g coconut oil, solid

1 ½ Tbsp toasted white sesame seeds

1 ½ Tbsp toasted black sesame seeds

2 large eggs

½ cup non-dairy milk of choice

2 Tbsp honey

Smoky Berry Jam

3 cups berries of choice

½ cup white sugar

½ tsp kosher salt

2 cups pecan or applewood chips

Instructions

Whisk together flour, sugar, salt, and baking powder.

Add coconut oil to the flour mixture and combine using either a food processor or a pastry blender until the mixture is crumbly. The mixture does not need to be completely evenly mixed, just as long as no giant chunks remain.

Add sesame seeds to the flour mixture, and stir to combine.

Whisk together eggs, milk, and honey until combined.

Add flour mixture to egg mixture and stir with a spatula until dough holds together. The dough will still be lightly crumbly, but when pressed together should hold shape.

Transfer dough to half sheet tray fitted with parchment paper. Press dough together to combine and shape into a round, flat, hockey disc shape roughly 2” tall.

Cut dough into 6 or 8 evenly sized triangles, moving them slightly to give room in between each scone.

Chill dough in the freezer for 10 minutes. This helps relax the gluten, which results in a more tender finished scone.

Preheat oven to 450F. Add wood chips.

Bake scones in the upper rack of the oven for 10-15 minutes, or until golden brown.

Remove scones from the oven and let rest 5 minutes.

Preheat grill to 450F.

Combine berries, sugar, and salt in an oven-safe skillet or small Dutch oven. Stir to combine.

Place skillet or Dutch oven on grill. Cover and let cook 10 minutes.

Reduce heat to 350F. Stir berry jam, taking care to scrape sides.

Cover and let cook another 15-20 minutes, or until the jam has reduced to desired consistency.

Remove jam from the grill. Puree or mash until desired consistency.

As someone who has only done big publisher traditional concepts (not to say I’ve not also had bad experiences!) this was fascinating as I’ve always suspected but never actually knew how these titles are put together. Brilliant post!

That was really interesting!!