Today’s newsletter is another special issue, a longer version of an op-ed I wrote for Prism last week!

On one of the first dates I had with my now-husband, we went to a brisket cooking competition in New York City. It was a very male-heavy affair, a bit like a grilling commercial come to life: dozens of chefs vying to be the next Brisket King, snapping their black latex gloves while slicing through juicy slabs of meat, sweating under the glow of yellow heat lamps as they extolled the delights of their particular beefy concoction to the guest-voters.

I don’t remember too much else from the night—I was, after all, still basking in the glow of the dating honeymoon period—except that I was miffed when my favorite pick, Butcher Bar in Astoria, didn’t win. And that almost every brisket recipe was heavily saturated with hefty flavorings—coffee, red wine, brown sugar, and the like. Besides vinegar and the occasional cameo of something bright like fresh ginger, I left the event with a distinct impression of what meat should taste like.

The only problem was, this flavor profile didn’t align particularly well with the composition that I naturally gravitated towards. A case in point: I had just begun cooking professionally for others, via multi-night popup dinners, and had recently served a guest a slice of beef cheek heavily spiced with floral and bright spices (I call them “top notes”). “This is delicious,” I recall them saying, “but it doesn’t taste like beef.”

To this day, I’m still not completely sure if that comment was meant to be a compliment or an insult. Either way, I couldn’t help but wonder: what is meat, and in particular beef, supposed to taste like? Which leads to a potentially more telling question: what is eating beef supposed to make me feel like?

Working through an answer to these questions has not at all been what I expected. First, I tackled it through a culinary lens, documenting the types of aromatics and spices found in rubs, marinades, or infused into the sauces of meat dishes. This helped me formulate a clearer understanding of what each ingredient was contributing to the overall blend.

In particular, I found classifying spices into “top,” “middle,” and “base” notes useful for developing understanding what flavor profiles presented themselves most commonly with meat. During the initial COVID lockdown, I spent some time organizing my entire spice closet through this lens, and it offered me a new perspective on what makes a spice blend truly standout. Top notes—like coriander, mace, and juniper—offer a bright bouquet on the nose and a bit of (metaphorical) sparkle on the tongue; middle notes—like star anise or fennel—are more mellow, providing a more neutral and warm structure. Most often, we see middle notes pop up in our foods with the presence of black pepper. In contrast, base notes—cinnamon, clove, allspice, and the like—are warm, toasty, sometimes smoky, and sit heavier on the tongue. (My husband likens their flavor to the sensation of dampness—not necessarily in the bad way.)

And why yes, I certainly noticed a pattern of spice usage when it came to red meats like beef: a deep proliferation of base notes. But why had our meat repertoire become so enamored with this specific flavor profile? I reflected back on my time nibbling (very delicious) burnt ends at Brisket King, on the occasions I suffered through dry slabs of prime rib at wedding buffets, on the days spent studying barbeque at culinary school, and began to parcel together a larger pattern: one that had less to do with the meat itself, and more with type of identity implicitly enshrined in meat. It finally clicked that eating meat was as much performance for self as it was for others, its very presence meant to be an inclusion, acceptance, even embrace of masculinity – and correspondingly, an implicit exclusion of people and concepts that didn’t feed into that construct. Maybe that was precisely why the flavors exalted of “real meat” — at least here in the States — were rarely ones I found myself drawn to.

These hunches became far more clear after I stumbled upon Carol J. Adams’ seminal book, The Sexual Politics of Eating Meat. In it, she argues that the act of meat-eating is not just about sustenance – it also bears strong attachments to the concept of masculinity and virility, thus making its presence (or lack thereof) another way to reinforce patriarchal oppression:

“the male prerogative to eat meat is an external, observable activity implicitly reflecting a recurring fact: meat is a symbol of male dominance.”

These days, where meat options are far more plentiful than in the past, and (generally speaking) men and women have reached parity in their ability to access and consume meat at their leisure, further categorization of meat is necessary to uphold this link of meat equals manliness. In particular, beef has become that battle flag. When manhood is “seen as a precarious state requiring continual social proof” (Vandello et al. 2008), studies find that men are more likely than women to “eat more meat than recommended,” and in particular “red meat [which] acts as a means to bolster dominant forms of masculinity,” especially when their gender identity was perceived to have been threatened. (Nakagawa, Hart 2019)

Enter Burger King’s 2006 “Manthem” commercial as a parodic — but also telling — example. In it, a large gaggle of hungry “real men” march down a cleared-out highway, holding up the new Texas Double Whopper in protest of “chick food” like quiches. Here, the mere consumption of beef is “a means for men to reassert traditional masculinity…through rejecting femininity.” (Buerkle 2009)

Most studies that look at the intersection of meat, red meat, and men will utilize women, “healthiness,” and vegetarian/veganism as the perceived antithesis of normative masculine ideals. (Notably, the level of rareness for meat can also be an important factor.) But I posit these social cues permeate one level further than just the meat or no meat binary, to how we prepare and flavor our “manly” associated meats. Buerkle mentions technique briefly in that “the common scenarios of men grilling outside [mean that] men employ fire, whereas women [cooking in the kitchen] use technology that distances them from men’s primordial methods.” But beyond the performance of cooking over open flame, this preparation also imparts a distinctive smokiness to the final product—which, perhaps because of the necessary action to achieve it, is also coded as masculine.

In contrast, red meat prepared in what is viewed as gentler, “healthier” (and thus, more “feminine”) methods like steaming or poaching generally receive far less fanfare. This is observable just by numbers alone: “grilled beef” returns with 1.2 billion results on quick Google search, compared to “steamed beef” at a paltry 46 million. Prowl through enough beef recipes, and another interesting pattern emerges: the flavor composition of beef recipes loosely categorized as “traditional American” (what that actually means is a debate for another day) tends to emphasize deep, musky, fatty additions like Worcestershire, cheese, and butter—a lot of butter.

This is all quite unfortunate given the actual versatility of beef. As Chef James Briscione shows in The Flavor Matrix, beef’s chemical composition works incredibly well paired with everything from floral notes (hyssop, angelica) and herbaceous options (eucalyptus, lovage), to tree fruits (pear, guava). Not to mention, this runs counter to a basic tenet of balance in cooking: lifting fatty ingredients with the addition of an acid (or tangy aromatics, or florals). Even as I made it a personal mission to break free from these social guardrails surrounding beef, the need to satisfy consumers who may already had pre-formed expectations weighed on me. In a one-shot situation like hosting popups (which I did for six years), it felt far easier to play by rules.

Recently, the social landscape around the role of beef, meat, and masculinity seems to have opened up for more diverse interpretations. Anecdotally, I'd point to factors like the success of the Instant Pot normalizing a moist cooking method for large cuts of meat, or the increasing number of successful female chefs who are unapologetic in their approach to cooking the way they want. Coupled with plant-based foods becoming increasingly mainstream — and thus more acceptable as a diet or lifestyle choice for men, too — perhaps the next few years will see beef finally freed from being an object of male performance.

After all, cooking is a deeply personal and creative process. I think what I’ve been searching for after all these years of jotting ideas down in a crinkly, oil-stained notebook without opportunities to ever test them out, is a sense of wonder–and possibility. When I now eat meat, and beef – which I always have, and intend to continue doing – I’m finally beginning to feel excited about what thoughtful meat preparation can be. And also, because a hyssop-dusted, guava-glazed ribeye sounds pretty darn delicious.

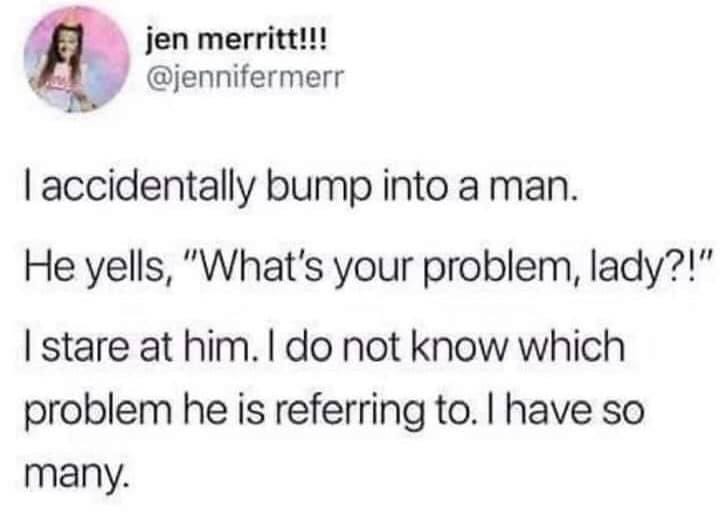

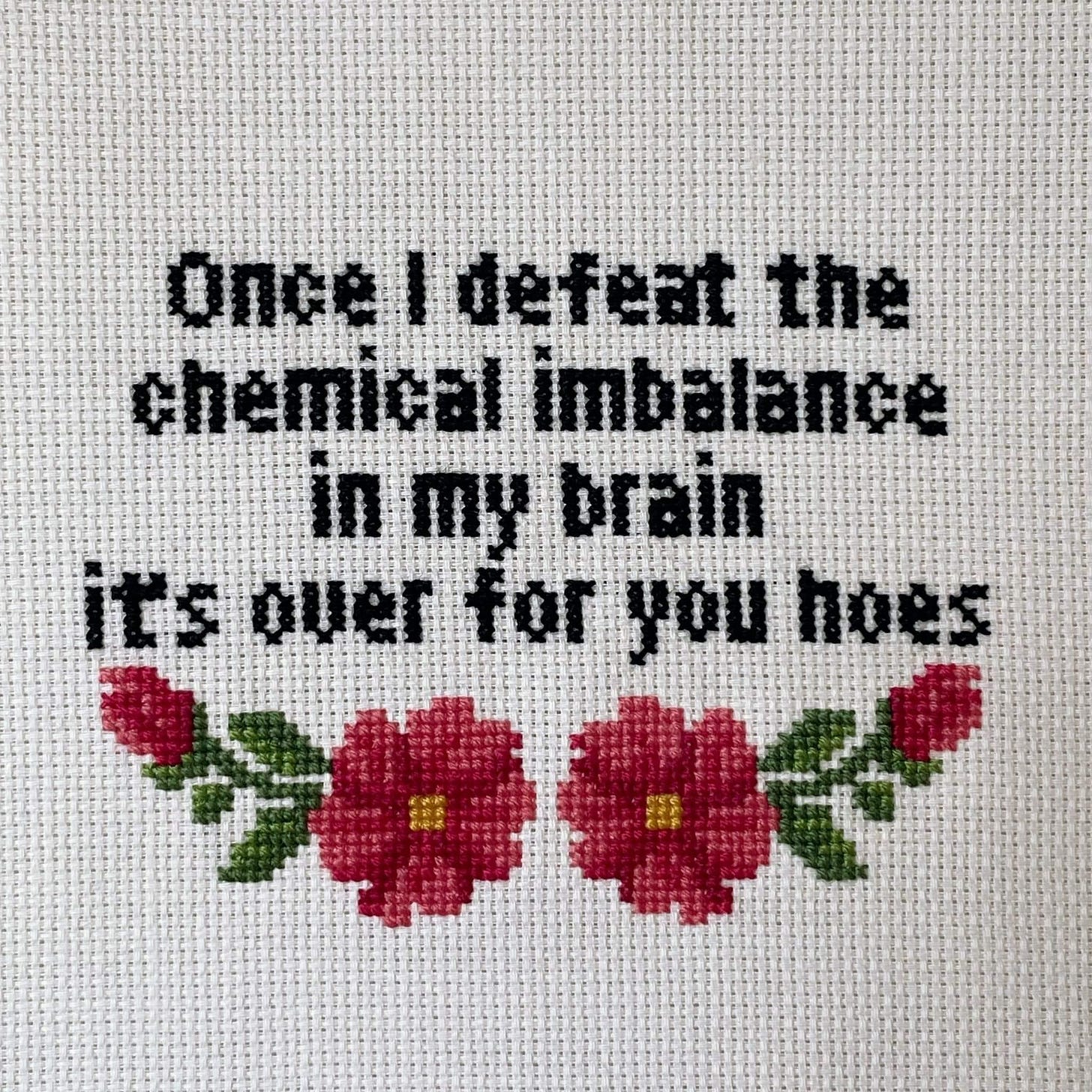

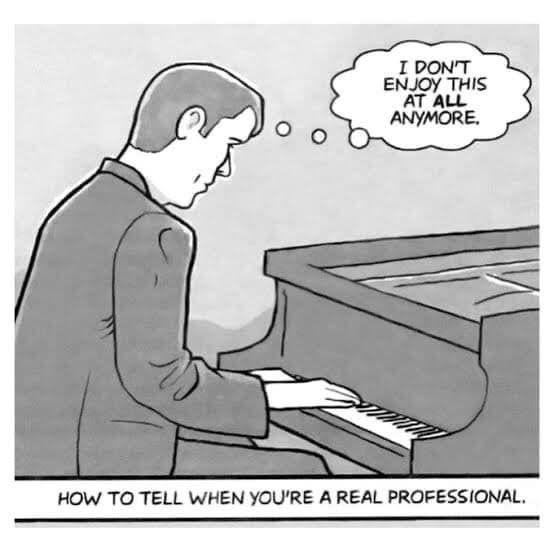

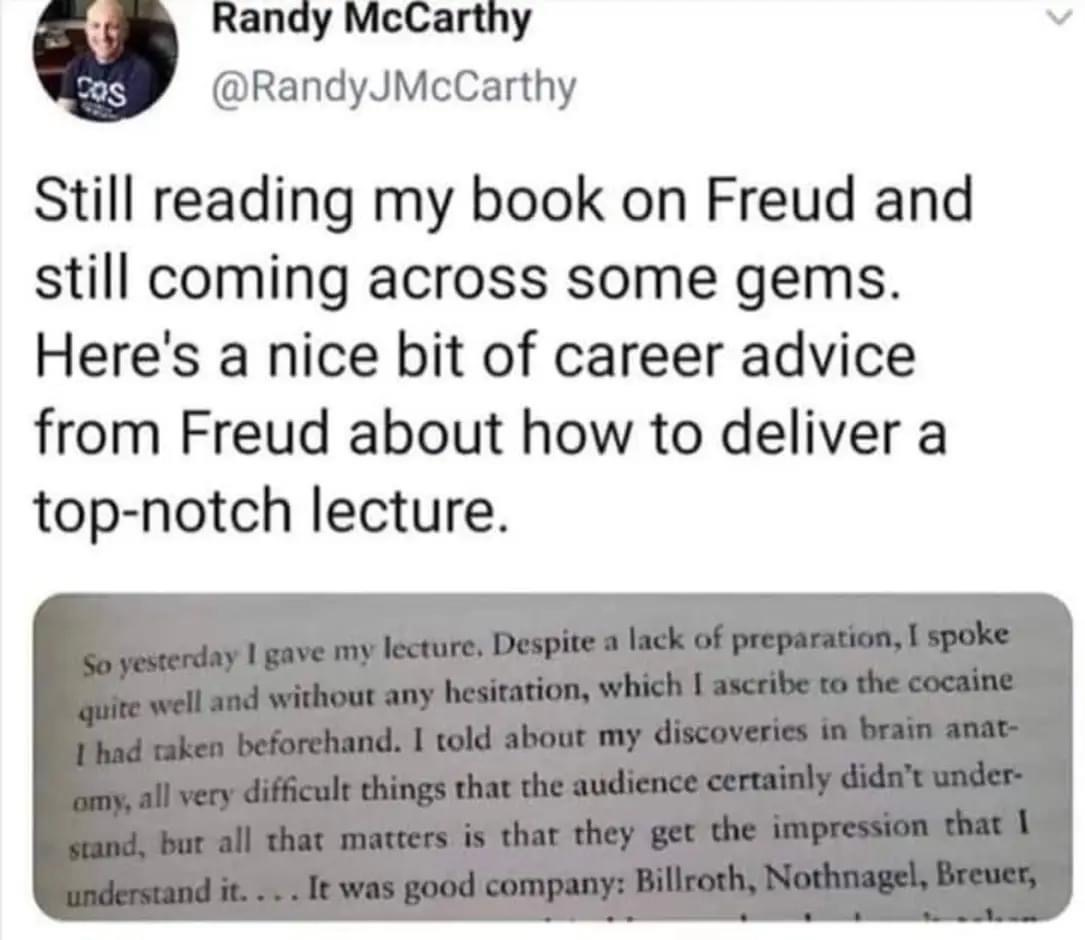

Weekly Meme Roundup

Personal Things From The Last Few Weeks

Listening to: Back to soft mandopop as I crank through moving boxes

Watching: Was slowly getting into The Wind Blows From Longxi but I have since semi-abandoned it…

(Still) Reading: All About Love by bell hooks

Eating: All my recipe tests for my upcoming chef residency at J Winery!

Drinking: Matcha lattes — here’s the recipe I made for EatingWell, though honestly you don’t need one

Nice thing I did for myself: Went and got a massage at my favorite place in LA!